I have an odd sort of problem. I know precisely how to be creative — I just don’t like to monetize it. I can spend all day inventing absurd limericks and silly poems, and I can draw cartoons and write short stories; I simply know how. But I have no wish to write advertisements. I don’t want to help corporations sell you products you don’t need. I don’t want to produce ‘content’ for you to ‘consume’, like a shrink-wrapped, discounted baked-goods in a supermarket.

Occasionally, as an act of morbid curiosity, I browse some sort of book about How To Be Creative and let me tell you, they really get my goat. The most popular ones are simply cleverly marketed nonsense. And often, somehow, written by psychologists. Would you read a cookbook on the strength of it being written by a psychologist? They’re not experts on cooking. And they’re not experts on creativity, either.

But you know, these books are cleverly marketed, and marinated in corpo-speak, and you know, when the market is saturated in nonsense, what choice do most people really have when they want to learn this stuff?

Remember, an expensive marketing campaign can sell just about anything. The book doesn’t need to be right or even helpful, as long as it seems to be those things. Consumers simply need to imagine they were helpful, so they can score those extra reviews at Amazon.

Let me offer an analogy. I sometimes have to buy running shoes, and an important quality I look for is durability. It’s reasonable, after all — who wants to keep replacing shoes every few months? Now, if consumerism concerned itself with merit — if it was a meritocratic system at all — then the best running shoes for consumers would be highly durable because … that’s what we want! But as you can see, consumerism doesn’t give a tinker’s cuss about durability. We want durable shoes, but shoe manufacturers aren’t here to furnish our needs — they simply want to sell a lot of shoes. Again, it’s not a meritocracy. But with a good-sized marketing budget and thousands of fake reviews, they can furnish us with the simulacrum of a meritocracy. We’re simply not supposed to notice.

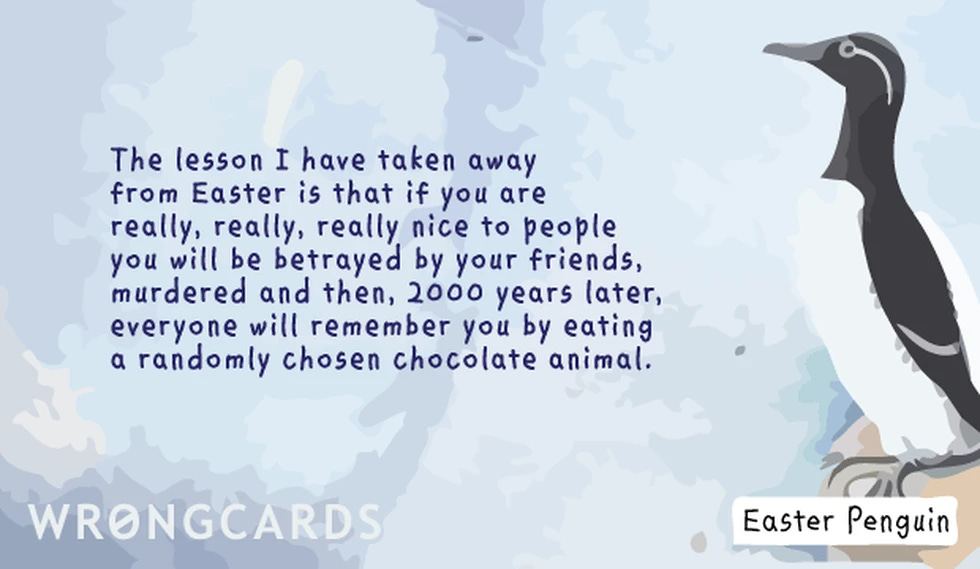

Let me interrupt myself. We’re a few days out from Easter and for logistical reasons I cannot offer to buy you chocolate (and by logistical, I actually mean ‘I somewhat ate all the chocolate, sorry about that, I have betrayed your trust, I know this, but in my defense I rather like chocolate’). Anyway, please accept this card that made for Wrongcards years ago, instead.

(source: me, at https://wrongcards.com/ecard/easter-lesson/ )

There’s a certain something to that card, isn’t there? Well, I’ve never been one to bludgeon a joke to death like a baby seal, but let’s do it anyway (if anyone asks, we’ll just say it was your idea). First off, the card is true. Why is that surprising? Well, you know, deep down, you and I are accustomed to getting lied to every day by marketing executives. Have you perused the greeting card aisle of a bookstore? (If you haven’t, don’t is my advice. These are dark days, and we must all try to keep our faith in humanity, no matter what.) We’re all so accustomed to hearing lies and nonstop drivel from organizations that whenever one seems straight-forward or honest about the world, we almost don’t know what to think.

I don’t know about you, but there’s something about that card, above, that makes me trust the artist. He’s a good guy, I somehow feel. I want to take him to a cafe and buy him a cup of tea, and possibly even a scone. Here is a man, I think, who tells the truth.

Similarly:

(source: me again, https://wrongcards.com/ecard/traditional-easter/ )

I don’t know about you, but I look at that card, above, and I think to myself, I wanna subscribe to this man’s newsletter. Well, I looked into and apparently you can do that! (Sometimes the world’s not so dark, after all).

But back to that card in particular … it’s true, isn’t it, that society doesn’t like unorthodox thinkers? In fact, if you look at all the Easter Wrongcards, you will be presented with the uneasy reminder that this holiday is, fundamentally, about a terrifically nice person who was rather poorly rewarded for being terrifically nice. I know, certain people have nonetheless chalked this up as a win for all nice people. I can’t help that. As another Wrongcard points out, God did not put me on this Earth to help people feel good about being wrong. (That is, if She really exists).

I’m abruptly reminded that Michael Bay made a movie called Pearl Harbor which obviously concerns the Japanese Imperial Navy attacking the United States on December 7, 1941. Now, despite the movie being called, you know, Pearl Harbor, the last hour of that film somehow centers itself around Americans bombing Japan. The film then ends on a triumphant note, even though nobody in that period of the war felt like the Allies were even slightly winning. But that’s modern American film-making for you. Which, not incidentally, is how I would describe modern-day Christianity’s approach to Easter. Or to put it another way, it’s terribly important to be a good and kind person have you bought enough chocolate eggs?

(I have no training in theology, I have merely glanced in its direction once or twice and have no wish to overburden myself with knowledge of the subject. The less I know, the easier it would be for me to get everything wrong — which is, ultimately, the point of Wrongcards, don’t you think?)

I believe I was talking about creativity. Let me tell you a thing. I’m showing you how to do it right now. Did you expect a Five-Point Plan? A series of bullet-points?

Whenever my mind thinks of creativity, I cannot help but think of the author, Nicolai Gogol, whom I read extensively when I was small. Gogol wrote a story called The Nose, in 1836, about a man who loses his nose. He sees it at some point and chases it down the street. It’s incredibly silly. One can write such things these days (I wouldn’t, of course; I am far too serious) but in 1836? That’s some edgy stuff for those times.

I read his unfinished novel, Dead Souls, when I was about 20, and it shocked me. On the first page of the novel, a few paragraphs into the story, is the following:

Presently, as the carriage was approaching the inn, it was met by a young man in a pair of very short, very tight breeches of white dimity, a quasi-fashionable frockcoat, and a dickey fastened with a pistol-shaped bronze tie-pin. The young man turned his head as he passed the carriage and eyed it attentively; after which he clapped his hand to his cap (which was in danger of being removed by the wind) and resumed his way.

The young man he describes in this passage never returns. His appearance is pure mischief and misdirection. Gogol is telling the Reader on the first page that you are in the company of a trickster. As you read Dead Souls, you discover the novel’s protagonist is ‘up to something’. He’s going around Russia, buying up the ownership papers of deceased serfs in Russia. But why? Why on Earth is he doing this for? There’s something that seems almost diabolical about the matter. Is he buying their souls in hell? (The Russian word for serf is the same as soul, you see). Perhaps it’s some sort of supernatural scam — but do we find out? Well, no, we’ll never know because Gogol burned the second half of his masterpiece in a fit of religious mania.

What evidently had scared the figurative hell out of Gogol was his own creativity. I would simply suggest that his theological framework offered him no useful explanation for his own abilities. He might even have been told his own mysterious genius was demonic. One might have argued that, within that specific framework, creating is a divine preoccupation, but … I don’t know if you’ve ever tried to discuss theology with anyone but what happens is that, well, everybody else’s insight into the mind of their Deity is far better than your own, and that’s all there is to say on the subject. You might as well go away and read a book about creativity written by a psychologist.

But what I can say is that it’s a good idea to have a decent framework in which to understand creativity, and how it works. Because goodness me, it’s a strange thing to do with one’s mind. It will feel like your own subconsciousness is talking through you, or perhaps your higher self. So, if you’re Hindu, you might assume Ātman is doing the yapping for you. Of course, Buddhists reject notions of Ātman, so you’re out of luck explaining it that way, if that’s your religion. You might instead feel the source of your creativity is some other entity — a hungry ghost or Mara or what have you. Yet regardless of all of this, the act of being creative will feel like you’re channeling something — if you’re good at it, that is — unless you’re a materialist, in which case you can only say to yourself something like, ‘well, isn’t the grey matter in my head a funny old thing?’ Though in my experience, materialism doesn’t seem to be a great foundation for creative work, because it seems to wall off a feeling of the Great Mystery Of It All, which, it turns out, is somewhat necessary for Practitioners of the Magical Creative Arts.

(For more information, please note the respective differences between the cathedrals of Europe built mid-12th until the 16th century, and those constructed in Post-Modernity — that is, after 1945. You’ll notice that recent cathedrals lack a certain whatsit, don’t they? As in, they don’t exactly inspire awe or wonder or reverence. This might be because our contemporary architects worship an altogether different god, so I suggest you let that one marinate.)

In broad strokes — and this is my first point today — we all need a framework, a set of theories that can lift our focus from our own squalid lives and outwards into the infinite expanse of the universe. There’s no brute-force involved here; on the contrary, you must make your mind the sort of place where ideas can arrive, like birds to a branch.

You see, our brains are the hardware. To take full advantage, we need — as individuals — to construct for ourselves a higher-functioning operating system that isn’t simply earthbound, utilitarian, and myopic. We can’t just think of ourselves as hardware, or be focused on banal tasks or preoccupations. We must be (it seems to me) at once pious and impious. We must be sufficiently mystical to be inventive, yet not get carried away and burn our own creations as heresies.

Now, listen — does any of this interest you? You see, a friend has been pestering me to write a book about ‘how I do all this stuff’ for about two years now, and I’m considering it. I’m just concerned that in order to write a proper book about creativity — or at least one that the publishing industry might understand — I’d have to subject myself to a lobotomy.

I’ll do it, if you’d find it useful or entertaining. I’ll write it all here and become one of those luminaries who go on book tours, and get into scandals, and smash up hotel rooms. Anything to get me out of the house, I suppose.

Anyway, I should wrap this up. By the way, here in Australia — a supposedly secular country — they’ve made Easter a four-day weekend. Yesterday, I walked two miles to buy bread and maybe a scone, and the bakery was closed. Participation in this holiday is mandatory, I gather. And somebody who was not Jesus seems to have decided that Jesus doesn’t want me to eat a scone. See, this is why I make wrongcards. You’re all very welcome.

With chaste affection,

Kris St.Gabriel

(source: me, yet again, https://wrongcards.com/ecard/our-unthanked-easter-benefactor/ )